Unsolved ’66: The Rock Star—Part 2

Valerie Percy’s killer murdered sixty-nine others, and it was covered up. (18th in a series)

“We got a request for a song by Bobby Fuller, my favorite rock star ever to have been murdered by gangsters.”

That introduction by musician Marshall Crenshaw precedes Crenshaw’s rendition of Fuller’s song “Julie” from Crenshaw’s album Live … My Truck Is My Home.

Though from different musical eras, the two share much musically. Fuller was a guitar player, singer, band leader, and songwriter. Crenshaw was doing the same when he released his first album sixteen years after Fuller died. The music of both draws comparisons to Buddy Holly, whose sound is present in some of Crenshaw’s and Fuller’s best-known work.

While I researched Fuller’s death, I was aware, if for no other reason than because I'm a fan, that some people believe he was the victim of a gangster. It was ruled an accident, but many have presumed it was a murder. Some people believe Morris Levy, who was president of Roulette Records, ordered it. Of course, Fuller and Levy were both in music: Fuller wrote and played it, and Levy packaged and sold it.

The theory goes that Levy wanted Bobby on the Roulette label. However, some sort of rub occurred, and Bobby was murdered.

Even by the standards of the US music industry, Levy was a crook. (A side note: Buddy Holly and his bandmates claimed they were swindled by their manager, Norman Petty, who, like Levy, stole royalty payments and put his name on songs he didn’t write.)

Bobby was allegedly unhappy with his record deal. This would surprise no one. Roger McGuinn of the Byrds, one of Bobby’s musical peers, has explained how terrible his own record deal was: a few pennies per LP sold. Ray Davies of the Kinks wrote about such deals in “The Moneygoround” with the lyrics “I only hope that I’ll survive.”

Morris Levy was convicted of extortion and is presumed, with his Genovese crime family associates, to have been behind the assault of a Pennsylvania record wholesaler who survived. However, Levy himself was no mobster.

More importantly, it’s hard to imagine why the mob or Levy would see it to be in their interests to murder Bobby Fuller. Even if Levy wanted Bobby at Roulette, what would murdering him achieve? This isn’t to say Levy was against using mob muscle when doing business in music. (More on that coming up.)

When mobsters murder, they murder other mobsters. The victims are never seen again, à la Jimmy Hoffa. Or if a body is not hidden, it’s to send a message to those within organized crime. Bobby Fuller’s battered body may well have resembled a mob murder—the type of hit meant to send a message. But if so, to whom? Paul Revere and the Raiders? Of course not.

At the time he was murdered, Bobby had a record deal. Morris Levy ran a record label. So Levy would have known, if he wanted to sign Bobby, he would have had to buy out Bobby's contract the way RCA obtained Elvis Presley from Sun Records a decade earlier. This isn't to say, for all his talent, Fuller in 1966 was the property that Presley was in 1955.

There are further reasons to doubt that Levy was behind Bobby Fuller’s murder: timing, for instance. Two and a half months before Bobby was slain, Levy signed Tommy James and the Shondells. At that time, James later said, numerous labels offered him a deal. But once he met with Levy, the other offers simply vanished.

In other words, Levy and his mob associates did not kill musicians; rather, they threatened music label executives. Later, when the Shondells racked up a string of hits, Levy stole millions from them the way Buddy Holly and his band said they were swindled (not by the mob). He simply stole their royalty payments.

James explained that he was a naive teenager when he was signed, the very type Levy sought to swindle. But in 1966, Bobby Fuller was no teenager. He knew how the business of music publishing royalties worked. This is reason to believe Levy would not have been interested in signing him.

Though Levy swindled him, James said Levy was supportive of his music and career. The truth is, had he masterminded Bobby’s murder, Levy would have to have been plotting it while he was helping the Shondells rush out their first album.

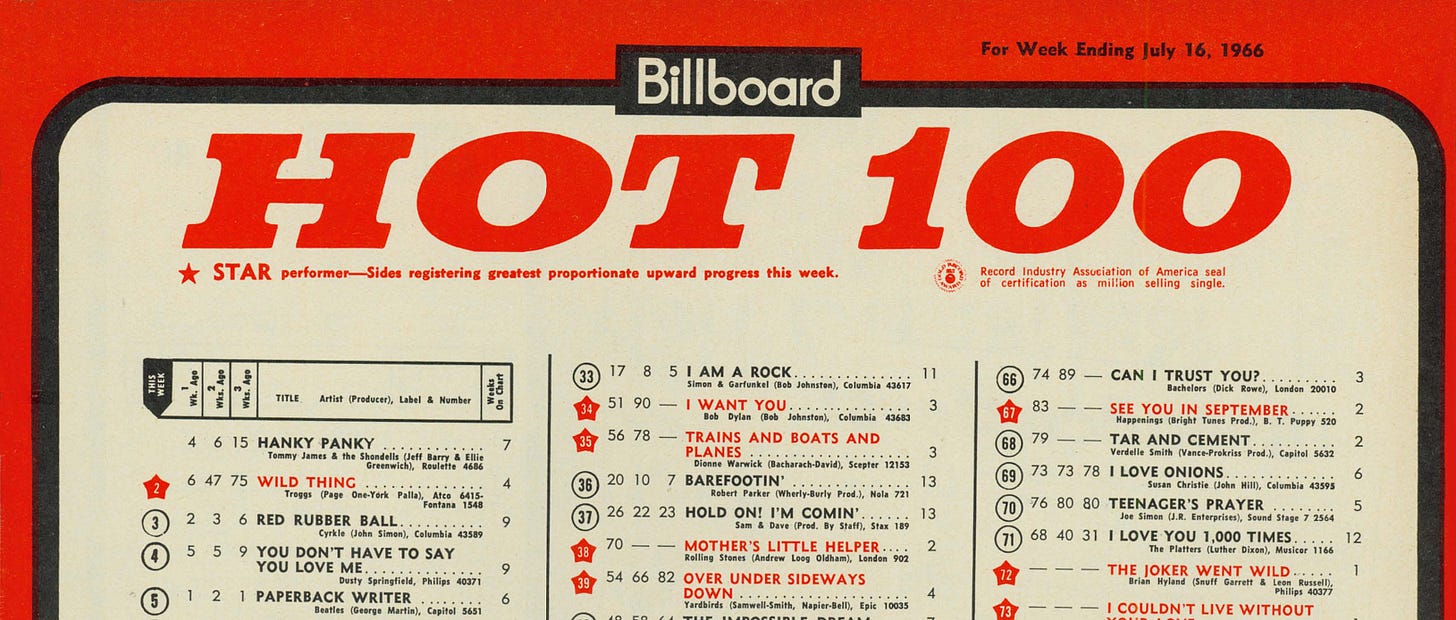

Starting in May 1966, that support helped push James’s first single, “Hanky Panky,” up Billboard’s Hot 100. The week of July 16, it knocked the Beatles’ “Paperback Writer” from the top slot. That’s right, the week before Bobby Fuller was murdered, supposedly by Morris Levy, Levy’s new act had the number one record in the nation.

Not only that, the week Bobby was murdered, James and Levy were still number one and, no doubt, celebrating it. I don’t know about you, but I have a hard time buying that Levy, who lacked motive to want Bobby murdered, would do so at such a time.

Meanwhile, Levy’s other businesses were booming. In addition to Roulette, he owned New York City nightclubs and record manufacturing plants, and he later acquired a record store chain.

Another reason to doubt that Levy murdered Bobby Fuller is the US music industry was run out of two regions. Industry insiders call them East Coast (New York) and West Coast (Los Angeles).

With few exceptions, prior to the late 1960s, East Coast acts were signed by East Coast labels and vice-versa. Levy ran an East Coast label. Bobby Fuller was a West Coast act.

Yet another reason to believe that Levy didn’t murder Bobby is Bobby’s biggest hit by far was “I Fought the Law”—a cover song. Had Levy been evaluating Bobby as an artist to sign, he would have learned that the royalty payments for his highest-charting single were owed to Sonny Curtis, who would not have allowed himself to be fleeced. This is why Levy looked to sign naive teenagers whose music publishing and money he could control.

In his autobiography, Tommy James reveals an encyclopedic knowledge of Morris Levy’s criminality and examines theories regarding Levy and crimes of violence, including that he was behind the murder of John Lennon, who at one time was involved in a multi-million dollar lawsuit with Levy. For good reasons, though, James dismisses it.

Meanwhile, Bobby Fuller is not mentioned in James’s book, not even in passing.

Over a number of years, I interviewed retired Chicago police homicide commander Joe DiLeonardi. In the course of discussing murder and mobsters, I told DiLeonardi that I remembered a seemingly endless number of news stories in the 1970s about mobsters’ bodies being found in cars at O’Hare Airport. To this DiLeonardi replied: “And many more,” while referring to the many other mob killings throughout the city. DiLeonardi worked a massive number of mob murder cases. One is featured in Joe D, Richard Whittingham’s biography of the storied cop.

What it reveals is the disciplined nature of twentieth-century mob murders in the US, which were carried out brazenly, targeted other mobsters, and often occurred in broad daylight, not at 4 a.m., the approximate time that Bobby Fuller left his apartment building.

There’s more that doesn’t fit the mob in Bobby’s murder. Mob hitmen don’t drive their victims’ bodies back to their victims’ homes after killing them; they don’t drive white cars, as it is believed Bobby’s killer did; and they don’t phone their targets at home just before killing them.

It also has been suggested that Bobby might have been murdered on orders of Bob Keane, president of Bobby’s record label, because Keane had an insurance policy on Bobby. But in 1959, Keane lost one of his stars, Richie Valens, in the crash that killed Buddy Holly. From then on, Keane routinely insured his acts.

Bobby Fuller’s brother Randy theorized that Bobby may have been set up with a phone call and the promise of attending a party. The call came a few hours before Bobby left home. Randy was correct.

But that's just one of the MOs that reveals who murdered Bobby, a killer who murdered more people than most mob hitmen did. There will be more on him to follow.

There’s more to this. You can learn it all starting here and please subscribe: