Unsolved ’66: Chicago Part 5

Valerie Percy's killer murdered sixty-nine others, and it was covered up. (26th in a series)

According to government sources, agents from the Department of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF) were in Chicago in 1989 to investigate the presumed murder of candy heiress Helen Brach, who vanished in 1977.

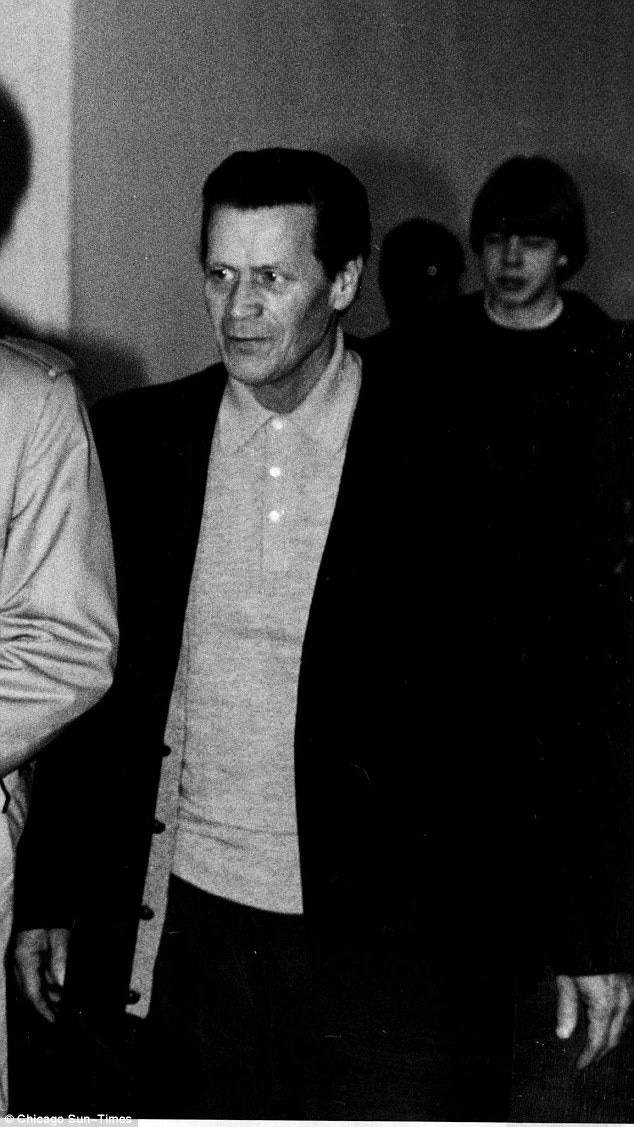

While doing so, they reportedly heard that Kenneth Hansen was responsible for the most infamous unsolved murder case in the city’s history. Three North Side boys, Robert Peterson and John and Anton Schuessler, were beaten, strangled, and left naked in a forest preserve ditch in 1955.

When Hansen was arrested thirty-nine years later, there were still Chicagoans who recalled how the murders shook the city and when the streets where the boys were last seen had been considered safe. In the years since, Hansen had made his living as a stableman before owning and operating a stables business of his own.

But what the stories announcing his arrest fail to mention is that Chicago police in the 1950s and beyond believed the murders were the first in a series of slayings—most of them unprecedented double or triple killings—that were perpetrated by the same killer and took six more lives before ending in March 1960.

The crimes couldn’t have come at a worse time for the city, which for a decade had been losing residents to the suburbs. Investigators from Chicago, the Illinois state police, and Cook County consulted with experts who identified unique evidence recovered by forensic examiners, leaving no stone unturned in their hunt for the boys’ slayer.

But at Hansen’s trial, the other slayings were kept in the distant past. According to the state, Hansen, who apparently lacked a record of violence, murdered the boys while working as a stableman for a disreputable horseman named Silas Jayne, who died in 1987.

Those following details of Hansen’s arrest read that Jayne’s stables, where the boys were purportedly slain, had been a hub for insurance fraudsters and men like Richard Bailey, a con man who, along with his brother, swindled rich widows like Helen Brach by selling them worn-out horses at outrageous prices.

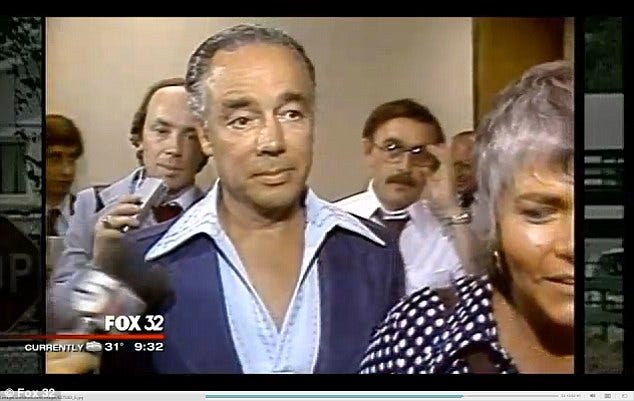

Silver-haired, smiling, and tanned, the smooth-talking Bailey was also a gigolo. More importantly, according to the state, he conspired to murder Brach. Bailey, who reportedly lied about swindling her, vehemently denied having had anything to do with Brach’s disappearance. Nonetheless, he was charged with conspiracy to commit murder in her case. Suspiciously, charges involving Bailey and Hansen made headlines at the same time.

According to the feds, Silas Jayne and his stables were central to unravelling two of Chicago’s greatest mysteries: the Peterson/Schuessler murders and the disappearance of Helen Brach. When it was over, Bailey was convicted of conspiracy to murder and sentenced to thirty years.

However, just as there was no evidence that Kenneth Hansen murdered the boys, the same can be said about Bailey conspiring to murder Brach, and not just because Brach’s body was never found, a fact that was fodder for gossip that mobsters incinerated it at an Indiana steel mill.

There are numerous reasons to believe that Brach’s houseman, Jack Matlick, an ex-con who looked like a killer from central casting, murdered Brach. Matlick said that he picked Brach up at O’Hare airport on Thursday, February 17, 1977, and she spent the weekend at home when, according to police, twenty-two phone calls were made to or from her Glenview estate.

Matlick dialed or answered all of them and told callers, including Richard Bailey, that Brach could not come to the phone. Meanwhile that weekend, Matlick had one of Brach's Cadillacs detailed and hired men to remove carpeting in a foyer of her home and repaint nearby walls. The workers did not see Brach that weekend, and she did not call anyone back. “Matlick also purchased a meat grinder, later telling police that he needed it to prepare food for Brach’s beloved dogs,” author James Ylisela wrote. All of this, Matlick claimed, had been requested by Brach.

The following Monday, Matlick, who failed two polygraph tests, said he drove Brach back to the airport for a flight to Fort Lauderdale. Yet there was no evidence that a ticket had been purchased for Brach or that she had planned to travel. Her friend Carol Stevens told police that she always picked up Brach at the airport. But Brach said nothing about a trip.

Meanwhile, over a dozen checks from Brach’s account totaling $13,117.40 were cashed. Her accountant said they were not signed by her. Two were used by Matlick to pay off his car loan and gambling debt. He maintained that Brach wrote them to him out of sympathy. Cook County judge Harry Budzinski, who in 1984 ruled Brach legally dead, said Matlick’s account of the weekend that she disappeared “totally lacks credibility.”

“Someone apparently wanted suspicion to fall on Bailey,” Ylisela wrote. Two bright red spray-painted messages purportedly appeared on roads near Brach’s home in 1978. “Bailey Killed Brach,” and “Richard Bailey Knows Where Mrs. Brach’s Body Is. Stop Him! Please!” If these messages really existed, there’s nothing to indicate they were anything more than writing on pavement.

I was in Chicago when the news that Bailey conspired to murder Brach and Hansen murdered the boys broke. Yet it seemed clear who murdered Brach, and there was nothing to indicate that Bailey was involved. Murder was not his MO, and he seemed too successful a swindler to have to kill anyone.

Suspiciously, Bailey’s conviction, like Hansen’s, seemed to be based on little more than stories told by witnesses—some with sketchy pasts—who claimed to have overheard Bailey implicate himself in Brach’s killing. Also like Hansen, Bailey appears to have lacked a record of violence.

Plus, what are the odds that in 1994—years before DNA was used to solve crimes—authorities would close not one but two stubbornly cold cases because ATF agents knocked on a few doors, this when local and state police moved heaven and earth in an effort to solve both over the years but could not?

The stories that Bailey conspired to murder Brach did not make sense. But in hindsight, they do. Prosecutors said they had no evidence tying Hansen to the Peterson/Schuessler murders, which reveals that they knew they had a thin case, to put it mildly.

But if the feds believed that William Thoresen murdered the boys and scores of others— and there are many reasons to believe that he did—and indicted Hansen as part of a cover-up of Thoresen’s crimes, Bailey was simultaneously charged for Brach’s murder in order to divert attention from the fact that the case against Hansen was, as his son Mark called it, a crock. Because Brach’s body was never found, her case would seem a natural for such a sham, which reeks of FBI skullduggery.

Anyone bothering to do the research will find that police believed whoever murdered the boys also murdered Judith Mae Anderson, the Grimes sisters, and three women at Starved Rock State Park—and it wasn’t Kenneth Hansen. There are many reasons to believe it was William Thoresen and that he, eight years after the Starved Rock killings, started calling himself the Zodiac while murdering in the San Francisco Bay Area.

This would also explain why, after Thoresen died in 1970, a cover-up was ordered and why, that decade, the feds had no interest in Red Wemette’s information about Hansen murdering the boys yet made it central to prosecuting Hansen in the 1990s.

There’s more to this. You can learn it all starting here and please subscribe:

At one time he called it his project. And it was all about getting rich quick. So i don,t see William Thoresen having had anything to do with the three boy,s But what you wrote about Matlick makes it very clear that he did the crime with money being the motive. 13,000 was huge in the 50,s